Autobiography | Thanks for the Ride

Thanks for the Ride

© 2020, 2023 by Vernon Miles Kerr, VernonMilesKerr.com

Introduction

An Autobiography of a Nobody Who Has Witnessed Amazing Things

June 2023

In 2020, faced by the likelihood that someone my age wouldn’t be around much longer, I started this autobiography—but was soon distracted. Now that my impending exit has been made even more likely, by a recent diagnosis involving a neuroendocrine carcinoma, I decided to pick it up again. Here’s what I remember of my 80 years of existence.

I intend this to be useful the reader (especially the young reader) and not for the glorification of the writer, who deserves none, whatsoever — measured by the normal yardsticks of wealth, fame, accolades, awards or even college degrees; all of which I have, exactly zero.

Moreover, here’s a caveat: These are not the memories of a normal socially-inclined, member of a standard demographic, but those of a paradoxical gregarious socializer, one moment, replaced by a congenital loner, a self-conceived outsider,

a frequent loser and an inveterate quitter —

more of an observer of the human saga than a participant —

not a born leader, but a pretty good follower, at least one who tries to be.

And, a compulsive writer of long, convoluted sentences; Charles Dickens, eat your heart out.) 😉

Given the foregoing, pathetic résumé, why in hell would you want to keep reading this? Well, there is one upside to a life of compulsive quitting driven by Attention Deficit Disorder and plain old lack of character: You get to experience a lot of interesting jobs, learn lots of interesting technology and develop some satisfying, useful and rewarding skills — all of which takes you to tons of interesting places and introduces you to multitudes of interesting people, mostly nice, but a few, not-so-nice.

So, in my little corner of earthly obscurity, I’ve bee richly blessed. Richly blessed.

How do I even begin? I learned the magic of reading while sitting on my mother’s lap at five. I experienced that “new car smell” that same year, when my father brought home a brand new 1949 Mercury – smoothly low, modern and painted a gorgeous dark maroon. I learned to love the soil of the Earth and it’s plants and creatures while in a high school Agriculture class on a ten acre farm in the middle of Ontario, California a large suburb—hemmed-in by other suburbs—of Los Angeles.

I’ve learned the piano, the guitar and the baroque recorder—at first, by musical notation and tablature, both of which I impatieintly abandoned, because I thought could play both instruents “by ear” with (to me) equally satisfiying results — and little effort. “Little effort,” will be a continuing them of this Autobiography.

I’ve learned to gracefully pilot skis, on both water and snow. I’ve learned how to take a sailboat through all the points of sailing — relishing in the “pop!” when fluttering sails suddenly fill, when “coming-about.” changing direction. I’ve learned to pilot an airplane — at least a few of the rudiments. I found the shuddering resistance of the air on the rudder and ailerons absolutely the same as that from the rudder of a sailboat. It was not unlike like the shudder of a fighting fish, sending a tingle up my arms and legs causeing a deep resonance in my psyche.

I’ve stood at the center of the Golden Gate Bridge, looking down on large passing ships, miniaturized by the great height of the span. I’ve deliberately tested my resistance to heat, to the point of dizziness by mowing the lawn at 120º, while living in Palm Springs, in the Sonoran Desert of California.

In my 20th year, a single year—as an inquisitive manager of newsboys, while I waited before each (often over-due) daily run of the paper’s presses — I learned the details of printing Newspapers, both in hot-lead and in photo-offset technologies — being blessed to be there, during the transition from Linotype to computerized type-composition and Photo-Offset printing. All the time I was hanging out in the press room, I was asking quetions — always questions. As a side note: our old 1930 Goss Web-Press was bought by a little paper in Roseville, California, now the center of my fight against Cancer. I wondered..”is the old black, ink-dripping, deafening Goss stilll being used?” I check the Roseville Tribune in the hotel’s rack…nah, the quality is now Photo-Offset — for sure.

Later, In my first job after dropping out of college, just before my Senior year, I learned the art of lending, credit verification and loan decision-making. I also learned the art of collections — how to get borrowers to do what they promised, without their wanting to kill me.

Another upside of this gut-spilling is that it makes a good, bad-object-lesson for young folks. By the way, I know that my writing style is old-fasioned and unnecessarily verbose, but I’m not gonna dumb it down for an intended younger audience. J.K. Rowling didn’t and it worked out fine for her (to put it mildly). Besides, the younger y’all are, the more tech-savvy and the more able to look these words up on Google. So, do it, dammit! 😀

To me, another thing which might make my life interesting, is that I seemed to be present at the conclusion of a lot of things; sort of like the opposite of a harbinger. Maybe everyone experiences that — but most just don’t notice it. But as we travel on — if you’re still with me — you’ll learn how I was there at, virtually the last minutes of existence, of technologies, churches, markets, occupations and even a few centuries-old trees. I’ll note these with the heading “The end of [fill-in blank] “

I plan to make this writing process publicly available, both here and via links from Twitter. As I add each chapter, I’ll append it directly below as an “update,” (in order to facilitate scrolling from top to bottom in chronological order). Thanks for listening. Cheers, Vern

June 3, 2023

Chapter One

Foundations

Somewhere, near a U.S. Army base in Texas, in July 1942, two sets of genetic material were combined and my life began. If anyone says the resulting single-celled zygote was not a “human being,” then they are denying I ever existed, irrespective of the plain words on this page.

At that moment, my father’s young army-recruits and draftees were enjoying blessed relief from their platoon sergeant’s rumbling, roaring, hovering presence. A bit of which (according to my mother) I would experience during his first visit to my crib-side, in Birmingham, Alabama, nine months later. “Quit that crying!” he roared, as if a two day-old wouldn’t take that as a signal to cry ever more frantically. But, more of that visit later.

Getting back to 1942, at my moment of conception Jews were being hidden in walls, loaded onto boxcars and secretly negotiating the Nazi-monitored transit system of Europe, in a desperate attempt to save their own lives. That cohort of fleeing Jews included a 7 year old boy, named Manfred Wolf, who figures prominently in this story and about whom, you’ll hear later. Also in-the-news that month, were words like El Alamein, Guadalcanal and stories of Nazi U-boats sinking ships in our nearby Gulf of Mexico and Gulf of St. Lawrence.

Before resuming with my post-natal story, a word about ancestors. Don’t worry, I’ll try to keep this short. I think just about every autobiographical work eventually gets around to discussing the “nature versus nurture” controversy. Can you really know the subject of any biography without some insight into both nature and nurture? How much does nature (DNA) affect one’s reaction to the challenges of life? More puzzling, how much does nature effect the manner — the way — in which parents nurture? There is no escapable answer but this: they are intertwined. The vignette showing an Army Sergeant bellowing at a two-day old baby is a case in point.

The Paternal Family: Kerrs and Browns

Perhaps this would be a good time to go ahead with the discussion of that side of the family. My paternal ancestors were Scots-Irish via my Grandpa, Miles Moore Kerr (who answered, “Scotch Irish” when, back in the 50s, I asked him about his ancestry. But Scottish people will tell you, Scotch is whiskey, Scots is their nationality.) Grandpa was descended from one of those wild Scottish-Borders clans, sent by James the First to try to convert Ireland to Protestantism. Apparently the ferocious Border Scots were only able to get as far as Ulster with King James’s scheme — but their fiery DNA made it all the way down to my grandpa, Miles, via one of his earlier great-great (dunno how many great) Grandpa Kerrs who fought under George Washington — according to several ancestry websites. And, according to the Daughters of the American Revolution, who welcomed my cousin’s daughter into their fold when she showed them her recent genealogy work.

Grandma Lucy Brown’s progenitors were of English, Choctaw Indian, and French Canadian (probably Cajun) extraction. The French part is reflected in her middle name. Brashears. Grandma’s mother was half-Choctaw which might explain Lucy’s serene, sometimes stoic demeanor. My Grandfather, a pious member of the rural Baptist church near their farm outside Antlers in Southeastern Oklahoma, was also an un-holy terror — and a cruel abuser at times. This according to my father’s eight siblings — my five aunts and three uncles — and also according to my father himself. My father, Arthur Vernon Kerr, more than once, related an incident to me, where Grandpa had beaten him so severely, he had to take him to an emergency-room in another county, to avoid damage to that pious reputation. Grandpa later kicked my father off the farm when he was 16, in the middle of the Great Depression, because he had impregnated his high school sweetheart. The expulsion was apparently another move made to protect that righteous public-persona.

But that harsh treatment might also have been the culmination of an on-going, jealous resistance that Miles had to Pop’s success in High School. Though only a sophomore at Antlers High School at the time, Pop was already a varsity football star , and the coach had told him he had already started working on getting my dad a full football scholarship to Oklahoma University, after graduation. Grandpa only had an 8th grade education and he would often proclaim, “That’s all anyone needs.” Banishment from the farm quashed Pop’s hope of that football scholarship — and caused my father to eschew not only football but all sports for the rest of his life. In my memory, with the exception of Golf in his retirement, I don’t remember Pop ever participating or even observing any sporting activity during his entire life, even TV sports. This lack of participation and even discussion of sports — including no father-son games of “catch” and other normal paternal sports interactions — is not only telling of his personality, but will also figure, later in this narrative, into examinations of my own psyche.

At this point I must deal with any cognitive dissonance the reader might have as to why my father gave me the middle name Miles, given his history with his father. I was not named after Grandpa — rather, Pop’s first cousin, and best friend, Miles Kerr, Cousin Miles was the son of Great Uncle Clyde Kerr, Grandpa’s brother). I was named after cousin Miles. Still confused? I don’t blame you.

Concluding with the Kerrs and Browns, let me add my summary of their DNA: I’ve often wondered why Grandma Lucy didn’t go all “momma-bear” on” Moore,” as she called him, when he physically beat both sons and daughters in his fits of Scots-Irish rage. Maybe she was just a bit too serene and stoic — a little bit, too Choctaw. Or maybe she was just as afraid of him as his children were. He was an enigmatic soul whom I was able to get to know, until about my second year of college more about Miles Moore Kerr later.

The Maternal Family: Norrises and Grigsbys

My mom was Lillian Cathryn Norris. My maternal roots were a mix of Grandpa Arthur Norris’s English ones and those of Grandma Bernice Grigsby’s English and German-by-way-of-Pennsylvania progenitors. The surname Norris, is found in the English Peerage, but since, according to my mother, he was born in Georgia then orphaned and reared by an aunt, I know of no way to connect him to that history. I know that he learned telegraphy, during his teen-years, near the close of the 19th Century, and was able to practice that new technology as a U.S. Army soldier, sent to Cuba during the Spanish-American war. Of that deployment, I know only two things: Mom said he was sending code one dark night in Cuba and, after hearing a rustle, stopped to peer outside his tent. He saw a large black jaguar silently padding through the camp. The other fact, according to my mother, is that he had a Cuban girlfriend, named Lolita. When my mother was born he wanted to name my mom Lolita, but (of course) my grandmother would have none of it—having previously endured my grandfather’s singing the praises of Lolita—quite often, apparently.

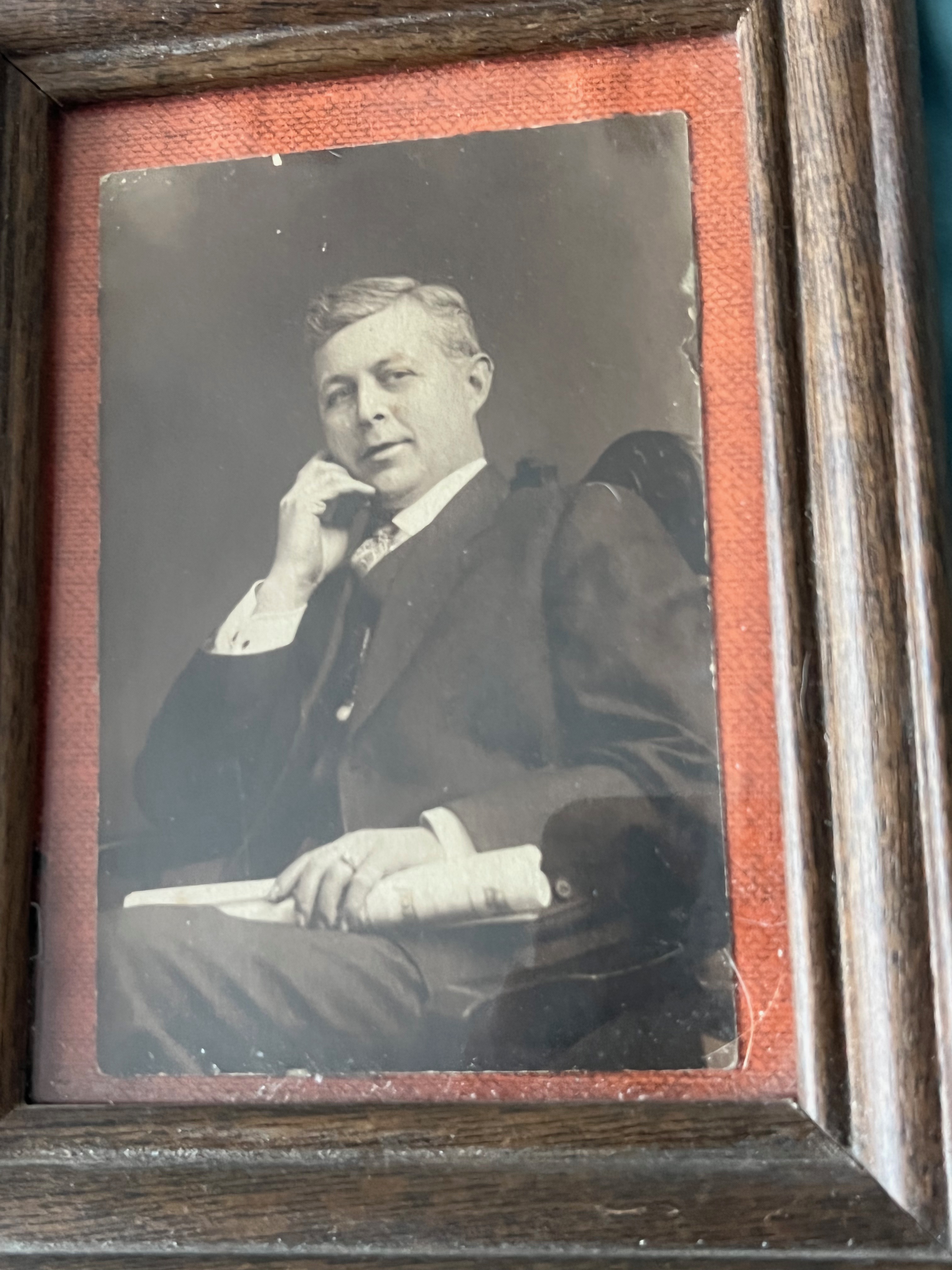

Grandma’s family were Grigsbys on the paternal side and Schneiders on the maternal. English, and Pennsylvania Dutch. Both families lived in and around Sullivan, Indiana at the time of her birth, and two of her siblings, George and Agnes had careers of note; another, Lillian, or “Aunt Lilly,” married a rich banker in Memphis. Great-uncle George Grigsby became an editor (Mom used to say “The Editor”) of the Indianapolis Star. We do have this professional photo portrait of him sitting suited, in a formal pose, with a rolled-up copy of the newspaper in his lap, but no other information.

Recently, while in Indianapolis on a project, a kind librarian graciously brought me roll-upon-roll of microfilm, from the Indy Star’s first decade in the 20th Century — but alas, the Star did not have the now-common block which lists the various members of a paper’s editorial staff. But, my reading the paper, and seeing the display ads from 1902, 1903, 1906 etc. was an enjoyable way to spend an afternoon in Indianapolis. Time well spent.

Grandma’s sister, Agnes Grigsby was one of America’s very first recording artists. Her operatic talents had somehow come to the attention of Thomas Edison and, as Agnes Kimball, she recorded many Edison Gramophone cylinders of opera music. Many of those are available on YouTube , currently. She actually still has Gen X and Millennial fans waxing eloquent in the comments of her profile.

Agnes died at 38, in the flu pandemic of 1918, three years before my mother was born. But Mom said Grandma Norris had a Gramophone in the living room and played Aunt Agnes’s cylinders often. “I wasn’t interested,” Mom told me once, “it sounded like a cat screeching to me.” I don’t know if that comment was prompted by the poor fidelity of the Gramophone’s large, curved megaphonic resonator, or the then-6-year-old’s lack of appreciation for the finer arts. No telling. And no telling what happened to that player and cylinders. By-the-way, my brother’s daughter, Sarah Rose Kerr Sweeny deserves credit for finding the information about Great Aunt Agnes’s recording career. Until Sarah discovered that, my mother always said, “Aunt Agnes was a professional singer and she did a tour with Victor Herbert’s orchestra once.” That’s all Mom knew, except hearing that “cat screeching” on the Gramophone.

I’ve always wondered if Grandma Norris had a bit of a complex, what with her siblings being such high-achievers and she, winding up a poor and simple housewife in Birmingham, Alabama. My memories of her, when I was five and six comprise a stern, often complaining, whining, presence. She was good to me though. I especially remember her hauling me along, on the clattering streetcar to Downtown Birmingham, eight miles, past the slag heaps and belching, stinking steel mills, to pay utility bills in person — and on one such trip, to see a play. It must have been the Nutcracker, as the one scene I recall was a troop of mushrooms bobbing away, up on stage.

If Grandma Norris’s irascibility was caused by an inferiority complex, vis-a-vis her siblings. I’m sure it was also highly exacerbated by Grandpa Norris’s leaving the deaconry of their Presbyterian congregation to study Geology and Evolution. I’m speculating that “the wife of a presbyter” in a church of presbyters must have been her sole remaining claim to status and social-standing. According to Mom, he made it worse, by writing letters to The Birmingham News, complaining about his former church’s old-fashioned reaction to his becoming a self-taught evolutionist and budding atheist. “I wish Daddy hadn’t done that,” she once told me.

I told you I would make this ancestry stuff short. Well thanks to my adult ADD, with its propensity to take detours, I lied. But thanks for hanging in there and please stay tuned, as I pick up the chronological part of this (whatever you wanna call it) later, in Chapter Two.

Chapter Two

The War Years

After Mom’s post-natal recuperation, she and I left Grandma’s little house in Birmingham, and joined my father, as he was shuttled back and forth across the country by rail, incubating platoon after platoon of warriors and sending each across the sea to fight Nazis. Little did I know, that three-quarters of a century later, the place of my nativity would be a breeding-ground for a new bunch of Nazis. But, I digress again.

Of course I shouldn’t have any memory of those 18 months of criss-crossing America by rail, following Pop from one army base to another, nor of that day when we saw him off, as he was deployed to Europe with his final cadre of trainees. But, I do have a memory of Mom and myself riding in an upper birth, curtain closed, she tucking a scratchy olive-drab army blanket around me and my hearing the “clackity-clackity—clackity-clackity” of the wheels and doppler-effect of the “ding-ding-ding-ding-dang-dang-dang-dang-dong-dong-donging” of grade-crossings flying by. That must have been when we went to meet our returning citizen-soldier in California after V-E day, maybe July of 1945. In those days soldiers were discharged at the place of their induction — and Pop’s induction had been in California in 1940. I would have been 27 months old on this train ride.

I have one other memory from prior to that. It was sitting on Grandma’s lap in a chair — in the middle of the front lawn for some reason — reading a children’s book. The memory of the colors is vivid. She turns a page. Later, I learned the reason that we were outside: I came across an old snapshot of that same scene with Grandma and I, sitting in the front yard reading the book and I realized that Mom’s little Kodak Brownie Box Camera had no flash attachment, so it was necessary to “reconstruct” interior scenes outside. Another snapshot of that time, has a nineteen-month-old me in front of a fully decorated Christmas tree, with my presents, out in the same yard. I suspect both of these “productions” were for the purpose of sending pictures to Pop and Grandma’s two sons, George and Arthur, all three of whom were then deployed somewhere in Europe.

Two years later, there’s a picture of a three-year-old me in front of a Christmas tree, taken with the same little box-camera inside our little Victory Square apartment in Taft, California. I remember my visiting, newly-minted veteran, Uncle George Norris, renting a flash-attachment at a local camera store. I also remember the store failed to provide the wire that led from the camera’s hot-shoe to the flash. No problem. The clever and ever-inventive, Uncle George improvised the needed connection with a butter knife and fork. That old picture is still around here, someplace, as I write this. But wait, there is one more fuzzy memory: We are in Birmingham and Grandma is ironing in the kitchen with her favorite flatiron, with the coal-burning, pot-bellied stove handy for re-heating it. Mom is there, they’re both crying. The radio is talking about President Roosevelt dying. But that’s seems impossible, since my second birthday was still a week in the future. Perhaps it was just a dream that caused a false memory.

During those years that our Kerr and Norris men were in Europe, so were all the other males from 18 through 45 in our Eastlake neighborhood of Birmingham. This made me quite a celebrity with girls on 4th Avenue South, teen-aged and younger. These are not memories, but rather my mother’s narrative. Nevertheless, this period of celebrity — as Mom placed me outside in a play-pen, most of every summer day, fully-exposed to my adoring female fans — is supremely causative of one of my most annoying, and ever-present-to-this-day character flaws: being a compulsive show-off. Some people develop precocious physical abilities, others early verbal skills. Mine was the latter. By seven months old, these bored bobby-soxers had taught me to sing the chorus to Judy Garland’s Trolley Song, “Ding, ding, ding goes da twah-weee…” and, apparently, a little salty language as well. Mom says that in an elevator in downtown Birmingham, yours-truly in arms, a lady exclaimed, “My what a cute little baby!” I reportedly smiled and sweetly replied, “Pee-pee, doo-doo, shit.” I was probably shocked at not having received the uproarious laughter that this line usually evoked.

This “creation,” this, little show-off, this self-conceived “alpha male,” is who greeted my returning father. Unfortunately — for our already-competitive relationship, dating back to that first crib-side meeting — our post-war reunion didn’t go so well. I’m sure that, to me, his towering presence and deep voice — along with his unwelcome interposition between Mom and me didn’t give me the best attitude toward him. His spanking me in a downtown department store, in full view of other shoppers, didn’t help either. Reportedly, I had thrown a fit after having been denied something I had snatched from a display. Pop’s reaction set some new ground rules: warranted, for sure—but to me, unwelcome of course.

VMK 9/4/2022